THE ENORMOUS QUANTITY OF DISPERSED PLASTIC will only break down after hundreds of years: a fact we now know, though it is difficult to picture its actual consequences. One project dedicated to collecting intact plastic objects from beaches, some even dating back 60 years ago, very clearly demonstrates why not knowing where plastic ends up is a problem. It is also a crucial subject because countries across the world are attempting to establish an international treaty by 2024 to reduce its presence in the environment and the sea.

A few years ago, Enzo Suma, a nature guide from Ostuni, in the Italian province of Brindisi, found a bottle of sun cream along the Salento coast. The bottle, showing a price in lira, was essentially in perfect state of preservation. Suma – who is 41 years old, studied Environmental Sciences and has worked in tourism since 2009 – photographed the bottle and posted it to Facebook. The item immediately garnered interest and it was found to date from the early 1970s. After this, Suma decided to launch the Archeoplastica project. Dedicated to the collection of plastic objects from beaches, dating as far back as 60 years ago, the project reconstructs their history. The aim is to raise people’s awareness about the need to reduce plastic use.

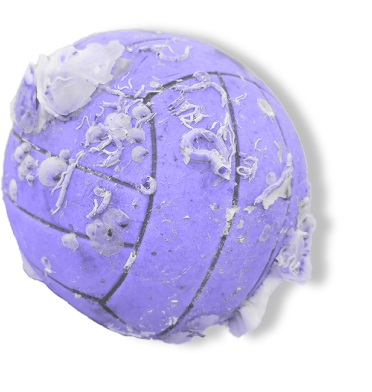

The stories told by Archeoplastica include eye drops sold in the 1960s and 1970s, in a container with a trapezoidal lid. Suma has found many specimens of the same bottle on Apulia’s beaches. The reason, explains the project, is that the advert for the eye drops recommended it be used for red eyes after swimming in the sea, to relieve irritation caused by the salty water.

The stories told by Archeoplastica include eye drops sold in the 1960s and 1970s, in a container with a trapezoidal lid. Suma has found many specimens of the same bottle on Apulia’s beaches. The reason, explains the project, is that the advert for the eye drops recommended it be used for red eyes after swimming in the sea, to relieve irritation caused by the salty water.

«EVEN AT SCHOOL WE WERE ALWAYS TOLD THAT PLASTIC LASTS CENTURIES AND CENTURIES. PERHAPS WE ARE DESENSITISED TO THIS INFORMATION AND UNABLE TO TRULY VISUALISE IT, SO WHEN THE SEA BRINGS US DECADES-OLD WASTE, IT AFFECTS US»

ENZO SUMA // ARCHEOPLASTICA

archeoplastica.itWe now know that the enormous quantity of plastic scattered in the environment and the sea will only break down after hundreds of years, it is difficult to picture its actual consequences, but the Archeoplastica project is helping.

In less than a century after its distribution, plastic is now one of the most commonly used materials. Its practicality and convenience have transformed our relationship with objects, paving the way for the “disposable” model. However, this transition has not been painless. The greatest cost has been paid by the environment: plastic is now found in every single ecosystem. This immense problem is becoming more and more urgent: 175 countries have decided to come together to establish a treaty and a joint policy on the issue by 2024.

Thanks to these negotiations, formal rules and directives will be set out to make the plastic cycle as traceable as possible, from the origin of the raw materials to the finished products, to their transformation into waste. Each country must implement regional, national and international measures to prevent plastic pollution, while eliminating current levels of plastic. But plastic waste is extensive, as shown partly by the Archeoplastica project.

Thanks to these negotiations, formal rules and directives will be set out to make the plastic cycle as traceable as possible, from the origin of the raw materials to the finished products, to their transformation into waste. Each country must implement regional, national and international measures to prevent plastic pollution, while eliminating current levels of plastic. But plastic waste is extensive, as shown partly by the Archeoplastica project.

Plastic is present in a myriad of products. And there is not just one kind of plastic. Since the 1950s, dozens of varieties have been developed, each with different characteristics and its own specific impact on the environment. We know they are there, but we do not yet know exactly where all these components end up, especially in terms of microplastics. This could pose a serious problem when defining the precise aims of the new treaty.

Even one of the most recent and relevant reports on plastic, produced by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (NASEM) in the United States, underlines the many gaps present in analysing the complete cycle of plastic, and in finding solutions to make it entirely recyclable. An urgent solution is needed for the lack of a system that is scientifically reliable to trace and keep under control the global dispersion of plastic, as well as to organise strategies to reduce its presence in the oceans.

In most countries, the plastic manufacturer must follow specific measures at the time of production, but there are no particular responsibilities once the plastic products are sold. For “disposable” plastic, for example, the responsibility falls on individuals. The essential problem is that there is no way of completely tracing the journey taken by a plastic product from production to landfill. And, if we do not know where the polymers found in the soil or water come from, it becomes very complicated to take action at the source of the problem.

In most countries, the plastic manufacturer must follow specific measures at the time of production, but there are no particular responsibilities once the plastic products are sold. For “disposable” plastic, for example, the responsibility falls on individuals. The essential problem is that there is no way of completely tracing the journey taken by a plastic product from production to landfill. And, if we do not know where the polymers found in the soil or water come from, it becomes very complicated to take action at the source of the problem.

In 2019, the Basel Convention added plastic waste to its list of hazardous waste: it is one of the most important international treaties on such practices. However, the document has never been signed by the United States, one of the world’s biggest producers of plastic waste. Mainly countries in South East Asia and Africa bear the burden of managing the large quantity of plastic waste produced in the world, without actually having the space or resources to dispose of it safely without impacting the environment. The countries involved are also those that suffer from the presence of large quantities of waste, which, for example, turns up along their coastlines once the plastic has travelled thousands of kilometres, floating about in the ocean.

THE COUNTRIES THAT CONTRIBUTE MOST TO OCEAN PLASTIC POLLUTION

SOURCE:Science.org / 2021

The regions of the tropical archipelago have higher plastic waste emissions due to their relatively small surface area compared to the length of their coastlines, in addition to high rainfall – which increases the likelihood that this type of waste will end up in the sea

To reduce this problem, satellite systems are being tested to track the movement of plastic that ends up in the environment and the sea. The satellite findings of the European Union’s Copernicus consortium, for example, help us identify the floating islands of plastic waste that form in the oceans and, when duly traced, can help us understand where they come from. However, experts say that the problem can only be resolved by reviewing the entire cycle of plastic use, by reducing its production as much as possible and improving the waste recovery and recycling systems.

The problem is that only a small portion of the plastic that ends up in separate waste collection is recycled: in Europe, this level is more or less 20 percent. The rest goes to landfill or is burned, because it is not convenient to recycle it or because there are not sufficient facilities to do so. In 2018, when China and other Asian countries reduced the quantity of plastic waste that they had previously been importing from Europe or North America, now forced to recycle or dispose of their plastic waste using alternative solutions, the problem was exacerbated.

The problem is that only a small portion of the plastic that ends up in separate waste collection is recycled: in Europe, this level is more or less 20 percent. The rest goes to landfill or is burned, because it is not convenient to recycle it or because there are not sufficient facilities to do so. In 2018, when China and other Asian countries reduced the quantity of plastic waste that they had previously been importing from Europe or North America, now forced to recycle or dispose of their plastic waste using alternative solutions, the problem was exacerbated.

177kg

WASTE FROM PLASTIC PACKAGING GENERATED ON AVERAGE IN 2020 BY EACH EUROPEAN CITIZEN

+20%

INCREASE IN THE ANNUAL QUANTITY OF PLASTIC WASTE GENERATED BY INDIVIDUAL EUROPEAN CITIZENS IN THE LAST TEN YEARS

20%

PLASTIC PRODUCED THAT IS RECYCLED IN EUROPE

14-18%

PLASTIC PRODUCED THAT IS RECYCLED AT GLOBAL LEVEL

30%

PLASTIC COLLECTED IN ITALY THAT IS RECYCLED

40%

PLASTIC COLLECTED IN ITALY THAT ENDS UP IN LANDFILL OR IS BURNED IN WASTE-TO-ENERGY PLANTS AND INCINERATORS

The various plastic recycling methods include mechanical recycling. After collecting and sorting the plastic, the product is washed then shredded into flakes, before being reused. However, each step of the process is onerous and often does not lead to the desired results. Plus, not all plastic is the same, but is made of different components that affect the recycling process, and in some cases exclude it entirely.

Plastic that is thrown away, even with separate waste collection, is often “impure”. This means that it has come into contact with food or factors that might compromise its recycling even after it has been washed and sorted. Unlike glass, plastic is not endlessly recyclable by nature.

The environmental impact caused by the difficulty of mechanically recycling plastic above all has an economic cost: according to a 2019 study published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, ocean plastic pollution has already cost 2500 billion dollars in wasted marine economic resources. ◗

The environmental impact caused by the difficulty of mechanically recycling plastic above all has an economic cost: according to a 2019 study published in the Marine Pollution Bulletin, ocean plastic pollution has already cost 2500 billion dollars in wasted marine economic resources. ◗

REUSING AND RECYCLING ARE FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES OF THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY, an economic model designed to be able to regenerate itself by maintaining a circular flow of materials for as long as possible. According to this approach, the items that we no longer use often are not simply waste to be disposed of (with all its complications, environmental damage and wastefulness), but products that, if regenerated, have new economic and environmental value. The end goal of the circular economy is to extract fewer and fewer natural resources to produce materials, limit pollution, reduce carbon dioxide emissions and fight climate change. Indicated as one of the tools to achieve the 17 Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations, the circular economy is based on four approaches (also called the 4 Rs): reduce, reuse, recycle and recover.

Reusing is the possibility to reuse products that have not yet become scrap or waste. It is preferable to repair or upcycle items, to avoid sending them to landfill, and to avoid the environmental consequences of recycling processes. Recycling, on the other hand, is the transformation of waste materials into so-called “secondary raw materials”, used in the production of new items.

Then there are the concepts of “reduce” and “recover”. The former refers in particular to producers of packaging, by incentivising the introduction of more streamlined products that avoid unnecessary material. “Recover”, on the other hand, refers to plants that burn waste – or that exploit its decomposition – to produce energy. This is considered the least sustainable solution, but it is still a better option than landfill. ◗

photos by archeoplastica

Reusing is the possibility to reuse products that have not yet become scrap or waste. It is preferable to repair or upcycle items, to avoid sending them to landfill, and to avoid the environmental consequences of recycling processes. Recycling, on the other hand, is the transformation of waste materials into so-called “secondary raw materials”, used in the production of new items.

Then there are the concepts of “reduce” and “recover”. The former refers in particular to producers of packaging, by incentivising the introduction of more streamlined products that avoid unnecessary material. “Recover”, on the other hand, refers to plants that burn waste – or that exploit its decomposition – to produce energy. This is considered the least sustainable solution, but it is still a better option than landfill. ◗

photos by archeoplastica